From Colonial Seeds to a Global Legacy

At White Peony, we highlight tea production in Sri Lanka because of our deep personal and professional connection to this island. Having spent years living and working in Ceylon, we’ve come to appreciate not only its legendary terroir but the soul it brings to every leaf. Our portfolio proudly includes Princess Sinhala, inspired by ancient island traditions, and Golden Leaf, a bold expression of Ceylon’s low-grown strength. We also honour Sri Lanka’s rising renown for white teas, especially the Silver Needle, handpicked at dawn from mist-covered gardens — a true jewel in the crown of island tea.

Nestled in the heart of the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka — formerly known as Ceylon — is now one of the world’s most renowned producers of tea. But this wasn’t always the case. The story of Ceylon tea is one of resilience, reinvention, and rich flavor — a tale that began not with tea, but with coffee.

From Coffee Catastrophe to Tea Renaissance

In the early 1800s, during British colonial rule, Sri Lanka’s central highlands were carpeted with coffee plantations. The crop thrived under British oversight until disaster struck in the form of a fungal disease known as coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) in the 1860s. Within a decade, the once-booming coffee industry collapsed.

But from this agricultural ruin rose a new star — tea.

In 1867, a Scottish planter named James Taylor took a bold step. On a 19-acre plot in Loolecondera Estate, near Kandy, he planted the island’s first experimental tea bushes. By 1872, he had set up Sri Lanka’s first tea factory and began exporting small quantities to England.

The gamble paid off. Tea proved not only resilient to the island’s climate but also adaptable to its hilly terrain and rich soil.

The Expansion of the Tea Industry

As the 19th century drew to a close, tea estates replaced the fallen coffee plantations. British planters and Indian Tamil laborers, brought to the island under harsh conditions, transformed the Central Highlands into an emerald quilt of meticulously pruned tea bushes.

Thomas Lipton, the Scottish grocer and entrepreneur, played a major role in popularizing Ceylon tea internationally. In the 1890s, he purchased large estates and introduced affordable, high-quality tea to the working class in Europe under his now-famous brand, Lipton.

By the early 20th century, Ceylon tea had become synonymous with quality — bold, brisk, and bright — and the country emerged as a key player in the global tea trade.

Post-Independence and the Birth of “Sri Lanka Tea”

After Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, the tea industry remained a backbone of the national economy. In 1972, the island officially became known as Sri Lanka, and “Ceylon Tea” became a geographical indication (GI) — a mark of origin and quality.

The 1970s also saw the nationalization of tea estates, placing them under government control. While this move aimed to support local farmers and restructure ownership, it introduced new challenges related to productivity and export competitiveness.

By the 1990s, many estates had been re-privatized or leased to private management companies, leading to modernization and renewed focus on quality.

The Unique Terroir of Sri Lankan Tea

Sri Lanka’s tea is not one monolith — it is a symphony of microclimates and altitudes. The country’s diverse terrain gives rise to several distinct tea-growing regions, each with its own flavor profile:

- Nuwara Eliya – High-grown, light-bodied, floral teas; often called the “champagne of Ceylon tea.”

- Uva – Aromatic, slightly tangy teas with a distinctive character.

- Dimbula – Balanced and mellow, ideal for afternoon sipping.

- Kandy – Stronger and brighter teas, often used in blends.

- Ruhuna and Sabaragamuwa – Low-grown, full-bodied, bold teas with deep color and richness.

This regional variation has helped Sri Lanka position itself as a producer of fine, artisanal teas, catering to connoisseurs worldwide.

Innovation and Sustainability in the 21st Century

Today, Sri Lanka is among the top five tea exporters globally, known for its orthodox processing method — a more traditional, labor-intensive technique that retains complex flavors and full leaves.

In recent decades, the industry has also seen:

- Growth in organic and fair trade teas.

- A rise in specialty teas such as white tea, silver tips, hand-rolled teas, and flavored blends.

- Increased focus on sustainable farming, biodynamic cultivation, and worker welfare.

Governmental and private initiatives like the Ceylon Tea Symbol of Quality (the lion logo) help preserve the island’s reputation, ensuring consumers receive authentic, high-grade tea.

Tea and Sri Lankan Identity

Beyond economics, tea is woven into the cultural identity of Sri Lanka. From roadside kiosks serving sweet milky brews to elegant plantation bungalows offering curated tastings, tea remains both a daily ritual and a national treasure.

Tea also plays a role in social cohesion and hospitality. Offering a cup of tea to a guest is a gesture of welcome across all communities — Tamil, Sinhalese, Muslim, and Burgher alike.

Conclusion: A Cup Steeped in History

The journey of Sri Lankan tea is a testament to human adaptability and nature’s generosity. From the ashes of coffee plantations to global renown, from colonial estates to local innovation, tea in Sri Lanka has evolved — but never lost its soul.

Whether sipped at sunrise overlooking misty hills, or enjoyed with friends in a city café, each cup of Ceylon tea carries with it the legacy of a land, a people, and a dragon-scented wind that once whispered over the Well of the East.

Luxury Tea Chest

Luxury Tea Chest  Collection Garnet Lucid

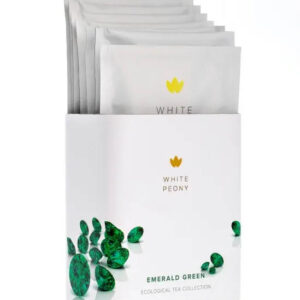

Collection Garnet Lucid  Collection Emerald Green

Collection Emerald Green  Mystica Cup Duo

Mystica Cup Duo